Least squares fitting with kmpfit¶

Introduction¶

We like code examples in our documentation, so let’s start with an example:

#!/usr/bin/env python

# Short demo kmpfit (04-03-2012)

import numpy

from kapteyn import kmpfit

def residuals(p, data): # Residuals function needed by kmpfit

x, y = data # Data arrays is a tuple given by programmer

a, b = p # Parameters which are adjusted by kmpfit

return (y-(a+b*x))

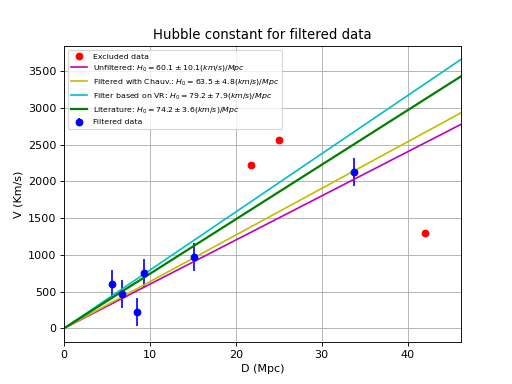

d = numpy.array([42, 6.75, 25, 33.8, 9.36, 21.8, 5.58, 8.52, 15.1])

v = numpy.array([1294, 462, 2562, 2130, 750, 2228, 598, 224, 971])

paramsinitial = [0, 70.0]

fitobj = kmpfit.Fitter(residuals=residuals, data=(d,v))

fitobj.fit(params0=paramsinitial)

print("\nFit status kmpfit:")

print("====================")

print("Best-fit parameters: ", fitobj.params)

print("Asymptotic error: ", fitobj.xerror)

print("Error assuming red.chi^2=1: ", fitobj.stderr)

print("Chi^2 min: ", fitobj.chi2_min)

print("Reduced Chi^2: ", fitobj.rchi2_min)

print("Iterations: ", fitobj.niter)

print("Number of free pars.: ", fitobj.nfree)

print("Degrees of freedom: ", fitobj.dof)

If you run the example, you should get output similar to:

Fit status kmpfit:

====================

Best-fit parameters: [414.71769219487254, 44.586628080854609]

Asymptotic error: [ 0.60915502 0.02732865]

Error assuming red.chi^2=1: [ 413.07443146 18.53184367]

Chi^2 min: 3218837.22783

Reduced Chi^2: 459833.889689

Iterations: 2

Number of free pars.: 2

Degrees of freedom: 7

In this tutorial we try to show the flexibility of the least squares

fit routine in kmpfit by showing examples and some background

theory which enhance its use. The kmpfit module is an excellent tool to demonstrate

features of the (non-linear) least squares fitting theory. The code examples

are all in Python. They are not complex and almost self explanatory.

kmpfit is the Kapteyn Package Python binding for a piece of software that provides a robust and relatively fast way to perform non-linear least-squares curve and surface fitting. The original software called MPFIT was translated to IDL from Fortran routines found in MINPACK-1 and later converted to a C version by Craig Markwardt [Mkw]. The routine is stable and fast and has additional features, not found in other software, such as model parameters that can be fixed and boundary constraints that can be imposed on parameter values. We will show an example in section Fitting Voigt profiles, where this feature is very helpful to keep the profile width parameters from becoming negative.

kmpfit has many similar

features in common with SciPy’s Fortran-based scipy.optimize.leastsq()

function, but kmpfit’s interface is more friendly and flexible and it is a bit faster.

It provides also additional routines to calculate confidence intervals.

And most important: you don’t need Fortran to build it because it is based

on code written in C.

Mark Rivers created a Python version from Craig’s IDL version (mpfit.py).

We spent a lot of time in debugging this pure Python code (after converting

its array type from Numarray to NumPy). It it not fast and we couldn’t get

the option of using derivatives to work properly. So we focused on the

C version of mpfit and used Cython

to build the C extension for Python.

A least squares fit method is an algorithm that minimizes a so-called objective function for N data points \((x_i,y_i), i=0, ...,N-1\). These data points are measured and often \(y_i\) has a measurement error that is much smaller than the error in \(x_i\). Then we call x the independent and y the dependent variable. In this tutorial we will also deal with examples where the errors in \(x_i\) and \(y_i\) are comparable.

Objective function¶

The method of least squares adjusts the parameters of a model function f(parameters, independent_variable) by finding a minimum of a so-called objective function. This objective function is a sum of values:

Objective functions are also called merit functions. Least squares routines also predict what the range of best-fit parameters will be if we repeat the experiment, which produces the data points, many times. But it can do that only for objective functions if they return the (weighted) sum of squared residuals (WSSR). If the least squares fitting procedure uses measurement errors as weights, then the objective function S can be written as a maximum-likelihood estimator (MLE) and S is then called chi-squared (\(\chi^2\)).

If we define \(\mathbf{p}\) as the set of parameters and take x for the independent data then we define a residual as the difference between the actual dependent variable \(y_i\) and the value given by the model:

A model function \(f(\mathbf{p},x_i)\) could be:

def model(p, x): # The model that should represent the data

a, b = p # p == (a,b)

return a + b*x # x is explanatory variable

A residual function \(r(\mathbf{p}, [x_i,y_i])\) could be:

def residuals(p, data): # Function needed by fit routine

x, y, err = data # The values for x, y and weights

a, b = p # The parameters for the model function

return (y-model(p,x))/err # An array with (weighted) residuals)

The arguments of the residuals function are p and data. You can give them any name you want. Only the order is important. The first parameter is a sequence of model parameters (e.g. slope and offset in a linear regression model). These parameters are changed by the fitter routine until the best-fit values are found. The number of model parameters is given by a sequence of initial estimates. We will explain this in more detail in the section about initial estimates.

The second parameter of the residuals() function contains the data. Usually this is a tuple with a number of arrays (e.g. x, y and weights), but one is not restricted to tuples to pass the data. It could also be an object with arrays as attributes. The parameter is set in the constructor of a Fitter object. We will show some examples when we discuss the Fitter object.

One is not restricted to one independent (explanatory) variable. For example, for a plane the dependent (response) variable \(y_i\) depends on two independent variables \((x_{1_i},x_{2_i})\)

>>> x1, x2, y, err = data

kmpfit needs only a specification of the residuals function (2). It defines the objective function S itself by squaring the residuals and summing them afterwards. So if you pass an array with weights \(w_i\) which are calculated from \(1/\sigma_i^2\), then you need to take the square root of these numbers first as in:

def residuals(p, data): # Function needed by fit routine

x, y, w = data # The values for x, y and weights

a, b = p # The parameters for the model function

w = numpy.sqrt(w) # kmpfit does the squaring

return w*(y-model(p,x)) # An array with (weighted) residuals)

It is more efficient to store the square root of the weights beforehand so that it is not necessary to repeat this (often many times) in the residuals function itself. This is different if your weights depend on the model parameters, which are adjusted in the iterations to get a best-fit. An example is the residuals function for an orthogonal fit of a straight line:

def residuals(p, data):

# Residuals function for data with errors in both coordinates

a, theta = p

x, y = data

B = numpy.tan(theta)

wi = 1/numpy.sqrt(1.0 + B*B)

d = wi*(y-model(p,x))

return d

Note

For kmpfit, you need only to specify a residuals function. The least squares fit method in kmpfit does the squaring and summing of the residuals.

Linearity¶

For many least squares fit problems we can use analytical methods to find the best-fit parameters. This is the category of linear problems. For linear least-squares problems (LLS) the second and higher derivatives of the fitting function with respect to the parameters are zero. If this is not true then the problem is a so-called non-linear least-squares problem (NLLS). We use kmpfit to find best-fit parameters for both problems and use the analytical methods of the first category to check the output of kmpfit. An example of a LLS problem is finding the best fit parameters of the model:

An example of a NLLS problem is finding the best fit parameters of the model:

A well-known example of a model that is non-linear in its parameters, is a function that describes a Gaussian profile as in:

def my_model(p, x):

A, mu, sigma, zerolev = p

return( A * numpy.exp(-(x-mu)*(x-mu)/(2.0*sigma*sigma)) + zerolev )

Note

In the linear case, parameter values can be determined analytically with straightforward linear algebra. kmpfit finds best-fit parameters for models that are either linear or non-linear in their parameters. If efficiency is an issue, one should find and apply an analytical method.

In the linear case, parameter values can be determined by comparatively simple linear algebra, in one direct step.

Goal¶

The function that we choose is based on a model which should describe the data so that kmpfit finds best-fit values for the free parameters in this model. These values can be used for interpolation or prediction of data based on the measurements and the best-fit parameters. kmpfit varies the values of the free parameters until it finds a set of values which minimize the objective function. Then, either it stops and returns a result because it found these best-fit parameters, or it stops because it met one of the stop criteria in kmpfit (see next section). Without these criteria, a fit procedure that is not converging would never stop.

Later we will discuss a familiar example for astronomy when we find best-fit parameters for a Gaussian to find the characteristics of a profile like the position of the maximum and the width of a peak.

Stop criteria¶

LLS and NLLS problems are solved by kmpfit by using an iterative procedure. The fit routine attempts to find the minimum by doing a search. Each iteration gives an improved set of parameters and the sum of the squared residuals is calculated again. kmpfit is based on the C version of mpfit which uses the Marquardt-Levenberg algorithm to select the parameter values for the next iteration. The Levenberg-Marquardt technique is a particular strategy for iteratively searching for the best fit. These iterations are repeated until a criterion is met. Criteria are set with parameters for the constructor of the Fitter object in kmpfit or with the appropriate attributes:

ftol- a nonnegative input variable. Termination occurs when both the actual and predicted relative reductions in the sum of squares are at mostftol. Therefore,ftolmeasures the relative error desired in the sum of squares. The default is: 1e-10

xtol- a nonnegative input variable. Termination occurs when the relative error between two consecutive iterates is at mostxtol. therefore,xtolmeasures the relative error desired in the approximate solution. The default is: 1e-10

gtol- a nonnegative input variable. Termination occurs when the cosine of the angle between fvec (is an internal input array which must contain the functions evaluated at x) and any column of the Jacobian is at mostgtolin absolute value. Therefore,gtolmeasures the orthogonality desired between the function vector and the columns of the Jacobian. The default is: 1e-10

maxiter- Maximum number of iterations. The default is: 200

maxfev- Maximum number of function evaluations. The default is: 0 (no limit)

A Fitter object¶

After we defined a residuals function, we need to create a Fitter object.

A Fitter object is an object of class Fitter. This object tells the fit

procedure which data should be passed to the residuals function. So it needs

the name of the residuals function and an object which provides the data.

In most of our examples we will use a tuple with references to arrays.

Assume we have a residuals function called residuals and two arrays x and y

with data from a measurement, then a Fitter object is created by:

fitobj = kmpfit.Fitter(residuals=residuals, data=(x,y))

Note that fitobj is an arbitrary name. You need to store the result

to be able to retrieve the results of the fit.

The real fit is started when we call method fit.

The fit procedure needs start values. Often the fit

procedure is not sensitive to these values and you can enter 1 as a value

for each parameter. But there are also examples where these initial estimates

are important. Starting with values that are not close to the best-fit

parameters could result in a solution that is a local minimum and not

a global minimum.

If you imagine a surface which is a function of parameter values and heights given by the the sum of the residuals as function of these parameters and this surface shows more than one minimum, you must be sure that you start your fit nearby the global minimum.

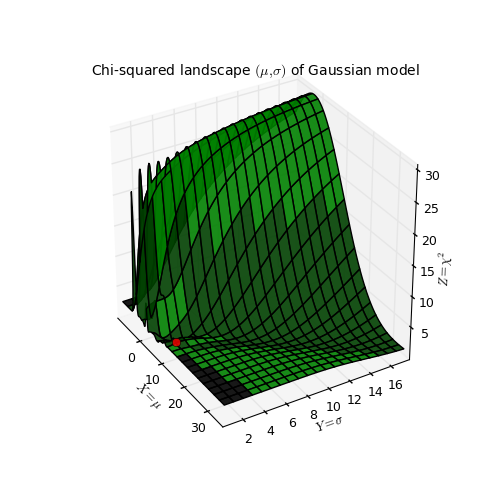

Example: kmpfit_chi2landscape_gauss.py

- Chi-squared landscape for model that represents a Gaussian profile

Chi-squared parameter landscape for Gaussian model. The value of chi-squared is plotted along the z-axis.¶

The figure shows the chi-squared parameter landscape for a model that represents a Gaussian. The landscape axes are model parameters: the position of the peak \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\) which is a measure for the width of the peak (half width at 1/e of peak). The relation between \(\sigma\) and the the full width at half maximum (FWHM) is: \(\mathrm{FWHM} = 2\sigma \sqrt{2ln2} \approx 2.35\, \sigma\). If you imagine this landscape as a solid surface and release a marble, then it rolls to the real minimum (red dot in the figure) only if you are not too far from this minimum. If you start for example in the front right corner, the marble will never end in the real minimum. Note that the parameter space is in fact 4 dimensional (4 free parameters) and therefore more complicated than this example. In the figure we scaled the value for chi-squared to avoid labels with big numbers.

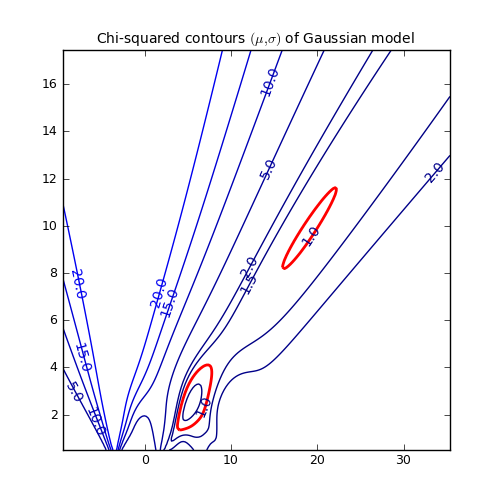

Another representation of the parameter space is a contour plot. It is created by the same example code:

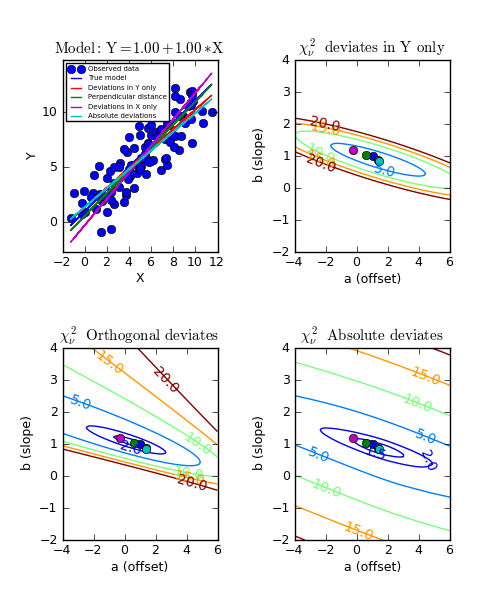

These contour plots are very useful when you compare different objective functions. For instance if you want to compare an objective function for orthogonal fitting with an an objective function for robust fitting.

Example: kmpfit_contours_objfunc.py

- Comparing objective functions with contour plots

A model which represents a straight line, always shows a very simple landscape with only one minimum. Wherever you release the marble, you will always end up in the real minimum. Then, the quality of the values of the initial estimates are not important to the quality of the fit result.

The initial estimates are entered in parameter params0. You can enter this

either in the constructor of the Fitter object or in the method fit().

In most examples we use the latter because then one can repeat

the same fit with different initial estimates as in:

fitobj.fit(params0=[1,1])

The results are stored in the attributes of fitobj.

For example the best-fit parameters are stored in fitobj.params.

For a list of all attributes and their meaning, see the documentation

of kmpfit.

An example of an overview of the results could be:

print("Fit status: ", fitobj.message

print("Best-fit parameters: ", fitobj.params)

print("Covariance errors: ", fitobj.xerror)

print("Standard errors ", fitobj.stderr)

print("Chi^2 min: ", fitobj.chi2_min)

print("Reduced Chi^2: ", fitobj.rchi2_min)

print("Iterations: ", fitobj.niter)

print("Number of function calls: ", fitobj.nfev)

print("Number of free pars.: ", fitobj.nfree)

print("Degrees of freedom: ", fitobj.dof)

print("Number of pegged pars.: ", fitobj.npegged)

There is a section about the use and interpretation of parameter errors in Standard errors of best-fit values. In the next chapter we will put the previous information together and compile a complete example.

A Basic example¶

In this section we explain how to setup a residuals function for kmpfit. We use vectorized functions written with NumPy.

The residual function¶

Assume we have data for which we know that the relation between X and Y is a straight line with offset a and slope b, then a model \(f(\mathbf{p},\mathbf{x})\) could be written in Python as:

def model(p, x):

a,b = p

y = a + b*x

return y

Parameter x is a NumPy array and p is a NumPy array containing the model

parameters a and b. This function calculates response Y values

for a given set of parameters and an array with explanatory X values.

Then it is simple to define the residuals function \(r(\mathbf{p}, [x_i,y_i])\) which calculates the residuals between data points and model:

def residuals(p, data):

x, y = data

return y - model(p,x)

This residuals function has always two parameters.

The first one p is an array

with parameter values in the order as defined in your model, and data

is an object that stores the data arrays that you need in your residuals function.

The object could be anything but a list or tuple is often most practical to store

the required data. We will explain a bit more about this object when we discuss

the constructor of a Fitter object.

We need not worry about the sign of the residuals because the

fit routine calculates the the square of the residuals itself.

Of course we can combine both

functions model and residuals in one function.

This is a bit more efficient in Python,

but usually it is handy to have the model function available if you need

to plot the model using different sets of best-fit parameters.

The objective function which is often used to fit the best-fit parameters of a straight line model is for example:

Assume that the values \(\sigma_i\) are given in array err, then this objective function translates to a residuals function:

def residuals(p, data):

x, y, err = data

ym = a + b*x # Model data

return (y-ym)/err # Squaring is done in Fitter routine

Another example is an objective function for robust (i.e. less sensitive to outliers) for a straight line model without weights. For robust fitting one does not use the square of the residuals but the absolute value.

We cannot avoid that the Fitter routine squares the residuals so to undo this squaring we need to take the square-root as in:

def residuals(p, data):

x, y = data

ym = a + b*x # Model data

r = abs(y - ym) # Absolute residuals for robust fitting

return numpy.sqrt(r) # Squaring is done in Fitter routine

Note

A residuals function should always return a NumPy double-precision floating-point number array (i.e. dtype=’d’).

Note

It is also possible to write residual functions that represent objective functions used in orthogonal fit procedures where both variables x and y have errors. We will give some examples in the section about orthogonal fitting.

Artificial data for experiments¶

For experiments with least square fits, it is often convenient to start with artificial data which resembles the model with certain parameters, and add some Gaussian distributed noise to the y values. This is what we have done in the next couple of lines:

The number of data points and the mean and width of the normal distribution which we use to add some noise:

N = 50

mean = 0.0; sigma = 0.6

Finally we create a range of x values and use our model with arbitrary model parameters to create y values:

xstart = 2.0; xend = 10.0

x = numpy.linspace(3.0, 10.0, N)

paramsreal = [1.0, 1.0]

noise = numpy.random.normal(mean, sigma, N)

y = model(paramsreal, x) + noise

Initial parameter estimates¶

Now we have to tell the constructor of the Fitter object what the residuals function is and which arrays the residuals function needs. To create a Fitter object we use the line:

fitobj = kmpfit.Fitter(residuals=residuals, data=(x,y))

Least squares fitters need initial estimates of the model parameters.

As you probably know, our problem is an example of ‘linear regression’ and this

category of models have best fit parameters that can be calculated analytically.

Then the fit results are not very sensitive to the initial values you supply.

So set the values of our initial parameters in the model (a,b) to (0,0). Use these values

in the call to Fitter.fit(). The result of the fit is stored in attributes

of the Fitter object (fitobj). We show the use of attributes

status, message, and params. This last attribute stores the ‘best fit’ parameters,

it has the same type as the sequence with the initial parameter (i.e. NumPy array, list or tuple):

paramsinitial = (0.0, 0.0)

fitobj.fit(params0=paramsinitial)

if (fitobj.status <= 0):

print('Error message = ', fitobj.message)

else:

print("Optimal parameters: ", fitobj.params)

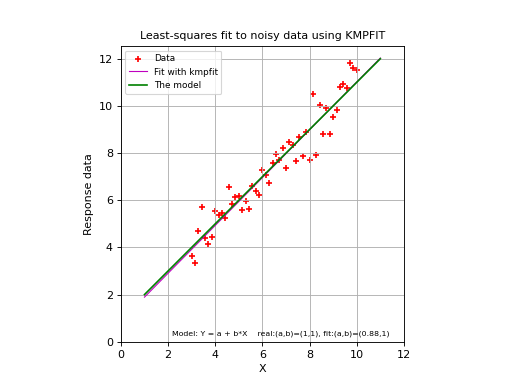

Below we show a complete example. If you run it, you should get a plot like the one below the source code. It will not be exactly the same because we used a random number generator to add some noise to the data. The plots are created with Matplotlib. A plot is a simple but effective tool to qualify a fit. For most of the examples in this tutorial a plot is included.

Example: kmpfit_example_simple.py - Simple use of kmpfit

#!/usr/bin/env python

#------------------------------------------------------------

# Purpose: Demonstrate simple use of fitter routine

#

# Vog, 12 Nov 2011

#------------------------------------------------------------

import numpy

from matplotlib.pyplot import figure, show, rc

from kapteyn import kmpfit

# The model

#==========

def model(p, x):

a,b = p

y = a + b*x

return y

# The residual function

#======================

def residuals(p, data):

x, y = data # 'data' is a tuple given by programmer

return y - model(p,x)

# Artificial data

#================

N = 50 # Number of data points

mean = 0.0; sigma = 0.6 # Characteristics of the noise we add

xstart = 2.0; xend = 10.0

x = numpy.linspace(3.0, 10.0, N)

paramsreal = [1.0, 1.0]

noise = numpy.random.normal(mean, sigma, N)

y = model(paramsreal, x) + noise

# Prepare a 'Fitter' object'

#===========================

paramsinitial = (0.0, 0.0)

fitobj = kmpfit.Fitter(residuals=residuals, data=(x,y))

try:

fitobj.fit(params0=paramsinitial)

except Exception as mes:

print("Something wrong with fit: ", mes)

raise SystemExit

print("Fit status: ", fitobj.message)

print("Best-fit parameters: ", fitobj.params)

print("Covariance errors: ", fitobj.xerror)

print("Standard errors ", fitobj.stderr)

print("Chi^2 min: ", fitobj.chi2_min)

print("Reduced Chi^2: ", fitobj.rchi2_min)

print("Iterations: ", fitobj.niter)

print("Number of function calls: ", fitobj.nfev)

print("Number of free pars.: ", fitobj.nfree)

print("Degrees of freedom: ", fitobj.dof)

print("Number of pegged pars.: ", fitobj.npegged)

print("Covariance matrix:\n", fitobj.covar)

# Plot the result

#================

rc('font', size=10)

rc('legend', fontsize=8)

fig = figure()

xp = numpy.linspace(xstart-1, xend+1, 200)

frame = fig.add_subplot(1,1,1, aspect=1.0)

frame.scatter(x, y, color='red', marker='+', label="Data")

frame.plot(xp, model(fitobj.params,xp), 'm', lw=1, label="Fit with kmpfit")

frame.plot(xp, model(paramsreal,xp), 'g', label="The model")

frame.set_xlabel("X")

frame.set_ylabel("Response data")

frame.set_title("Least-squares fit to noisy data using KMPFIT", fontsize=10)

s = "Model: Y = a + b*X real:(a,b)=(%.2g,%.2g), fit:(a,b)=(%.2g,%.2g)"%\

(paramsreal[0],paramsreal[1], fitobj.params[0],fitobj.params[1])

frame.text(0.95, 0.02, s, color='k', fontsize=7,

ha='right', transform=frame.transAxes)

frame.set_xlim(0,12)

frame.set_ylim(0,None)

frame.grid(True)

leg = frame.legend(loc=2)

show()

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

Function simplefit()¶

For simple fit problems we provide a simple interface. It is a function which is used as follows:

>>> p0 = (0,0)

>>> fitobj = kmpfit.simplefit(model, p0, x, y, err=err, xtol=1e-8)

>>> print(fitobj.params)

Argument model is a function, just like the model in the previous section.

p0 is a sequence with initial values with a length equal to the number of parameters

that is defined in your model. Argument x and y are the arrays or lists that represent

your measurement data. Argument err is an array with 1 \(\sigma\) errors,

one for each data point. Then you can enter values to tune the fit routine

with keyword arguments (e.g. gtol, xtol, etc.).

In the next example we demonstrate how to use lists for your data points,

how to make an unweighted fit and how to print the right parameter uncertainties.

For an explanation of parameter uncertainties, see section Standard errors of best-fit values.

The advantages of this function:

You need only to worry about a model function

No need to create a Fitter object first

Direct input of relevant arrays

As a result you get a Fitter object with all the attributes

It is (still) possible to tune the fit routine with keyword arguments, no limitations here.

Example: kmpfit_example_easyinterface.py

- Simple function

#!/usr/bin/env python

#------------------------------------------------------------

# Purpose: Demonstrate simple use of fitter routine

#

# Vog, 24 Nov 2011

#------------------------------------------------------------

import numpy

from matplotlib.pyplot import figure, show

from kapteyn import kmpfit

# The model:

def model(p, x):

a, b = p

y = a + b*x

return y

# Artificial data

N = 50 # Number of data points

mean = 0.0; sigma = 0.6 # Characteristics of the noise we add

x = numpy.linspace(2, 10, N)

paramsreal = [1.0, 1.0]

noise = numpy.random.normal(mean, sigma, N)

y = model(paramsreal, x) + noise

err = numpy.random.normal(mean, sigma, N)

# Simple interface

p0 = (0,0)

xl = list(range(10))

yl = [k*0.5 for k in xl]

fitobj = kmpfit.simplefit(model, p0, xl, yl)

print("Best fit parameters:", fitobj.params)

print("Parameter errors: :", fitobj.stderr)

fitobj = kmpfit.simplefit(model, p0, x, y, err=err, xtol=1e-8)

print("Best fit parameters:", fitobj.params)

print("Parameter errors: :", fitobj.xerror)

fitobj = kmpfit.simplefit(model, p0, x, y, maxiter=100)

print("Best fit parameters:", fitobj.params)

print("Parameter errors: :", fitobj.stderr)

Standard errors of best-fit values¶

With the estimation of errors on the best-fit parameters we get an idea how good a fit is. Usually these errors are called standard errors, but often programs call these errors also standard deviations. For nonlinear least-squares routines, these errors are based on mathematical simplifications and are therefore often called asymptotic or approximate standard errors.

The standard error (often denoted by SE) is a measure of the average amount that the model over- or under-predicts.

According to [Bev] , the standard error is an uncertainty which corresponds to an increase of \(\chi^2\) by 1. That implies that if we we add the standard error \(\sigma_i\) to its corresponding parameter, fix it in a second fit and fit again, the value of \(\chi^2\) will be increased by 1.

The next example shows this behaviour. We tested it with the first parameter fixed and

a second time with the second parameter fixed. The example also shows how to set

parameters to ‘fixed’ in kmpfit.

The model is a straight line. If you run

the example you will see that it shows exactly the behaviour as in

(7). This proves that the covariance matrix (explained later)

of kmpfit can be used to

derive standard errors.

Note the use of the parinfo attribute of the Fitter object to fix

parameters. One can use an index to set values for one parameter or one can set

the values for all parameters. These values are given as a Python dictionary.

An easy way to create a dictionary is to use Python’s dict() function.

Example: kmpfit_errors_chi2delta.py

- Meaning of asymptotic errors

#!/usr/bin/env python

#------------------------------------------------------------

# Purpose: Demonstrate, using kmpfit, that if you find best-fit

# parameters, the errors derived from the covariance matrix

# correspond to an increase in chi^2 of 1.

# Vog, 23 Nov 2011

#------------------------------------------------------------

import numpy

from matplotlib.pyplot import figure, show, rc

from numpy.random import normal, randint

from kapteyn import kmpfit

def residuals(p, data):

x, y, err = data

a, b = p

model = a + b*x

return (y-model)/err

# Artificial data

#----------------

N = 100

a0 = 2; b0 = 3

x = numpy.linspace(0.0, 2.0, N)

y = a0 + b0*x + normal(0.0, 0.4, N) # Mean,sigma,N

derr = normal(0.0, 0.5, N)

err = 0.9+derr

fitobj = kmpfit.Fitter(residuals=residuals, data=(x, y, err))

fitobj.fit(params0=[1,1])

if (fitobj.status <= 0):

print('error message =', fitobj.errmsg)

raise SystemExit

print("\n\n======== Results kmpfit for Y = A + B*X =========")

print("Params: ", fitobj.params)

print("Errors from covariance matrix : ", fitobj.xerror)

print("Uncertainties assuming reduced Chi^2=1: ", fitobj.stderr)

print("Chi^2 min: ", fitobj.chi2_min)

p1, p2 = fitobj.params

e1, e2 = fitobj.xerror

# Next we take one of the parameters to be fixed and change its value

# with the amount of one of the estimated errors (covariance, scaled or bootstrap)

# If we fit again, then, according to Bevington (Data Reduction and Error

# Analysis for the Physical Sciences Section 11-5), one should expect the

# Chi square value to increase with 1.0

fitobj.parinfo[0] = dict(fixed=True)

fitobj.fit(params0=[p1+e1,1])

print("\nFix first parameter and set its value to fitted value+error")

print("Params: ", fitobj.params)

print("Chi^2 min: ", fitobj.chi2_min)

print("Errors from covariance matrix : ", fitobj.xerror)

fitobj.parinfo = [{'fixed':False}, {'fixed':True}]

fitobj.fit(params0=[1, p2+e2])

print("\nFix second parameter and set its value to fitted value+error")

print("Params: ", fitobj.params)

print("Chi^2 min: ", fitobj.chi2_min)

print("Errors from covariance matrix : ", fitobj.xerror)

The results for an arbitrary run:

======== Results kmpfit for Y = A + B*X =========

Params: [2.0104270702631712, 2.94745915643011]

Errors from covariance matrix : [ 0.05779471 0.06337059]

Uncertainties assuming reduced Chi^2=1: [ 0.04398439 0.04822789]

Chi^2 min: 56.7606029739

Fix first parameter and set its value to fitted value+error

Params: [2.0682217814912143, 2.896736695408106]

Chi^2 min: 57.7606030002

Errors from covariance matrix : [ 0. 0.03798767]

Fix second parameter and set its value to fitted value+error

Params: [1.9641675954511788, 3.0108297500339498]

Chi^2 min: 57.760602835

Errors from covariance matrix : [ 0.0346452 0. ]

As you can see, the value of chi-square has increased with ~1.

Standard errors in weighted fits¶

In the literature [Num] we can find analytical expressions for the standard errors

of weighted fits for standard linear regression. We want to discuss the

derivation of analytical errors for weighted fits to demonstrate that these errors

are also represented by the elements of the so-called variance-covariance matrix

(or just covariance matrix),

which is also a result of a fit with kmpfit (attribute Fitter.covar).

How should we interpret these errors? For instance in Numerical Recipes, [Num]

we find the expressions for the best fit parameters of a model \(y=a+bx\)

Use the chi-squared objective function:

To find analytical expressions for the best-fit values of a and b, we need to take derivatives of this objective function:

Define:

Then one can rewrite (9) into:

which is in matrix notation:

If we define:

which gives the solution:

Define:

The solutions for a and b are:

For the standard errors we will derive the error in parameter a and b. The error in a is by the law of propagation of errors:

>From (16) and (10) we derive:

With (17) we find

Applying the same procedure to b:

With (17) we find

To summarize:

A classical implementation to find analytical best-fit parameters using NumPy is as follows:

def lingres(xa, ya, err):

w = numpy.where(err==0.0, 0.0, 1.0/(err*err))

Sum = w.sum()

sumX = (w*xa).sum()

sumY = (w*ya).sum()

sumX2 = (w*xa*xa).sum()

sumY2 = (w*ya*ya).sum()

sumXY = (w*xa*ya).sum()

delta = Sum * sumX2 - sumX * sumX

a = (sumX2*sumY - sumX*sumXY) / delta

b = (sumXY*Sum - sumX*sumY) / delta

siga = numpy.sqrt(abs(sumX2/delta))

sigb = numpy.sqrt(abs(Sum/delta))

return a, b, siga, sigb, delta, Sum, sumX2, sumX

Note that these formulas are susceptible to roundoff error and Numerical Recipes derives alternative formulas (Section 15.2). However, our functions work with double precision numbers and we didn’t (yet) encounter a situation where roundoff errors were obvious.

If we compare these results with the elements of the covariance matrix in (13), then we observe that the expressions for the parameter variances, are the square root of the diagonal values of this matrix. The co-variance between a and b can be calculated also and the formula turns out to be the same as the off-diagonal elements of the covariance matrix. This value is:

It is easy to demonstrate that these errors are the same as those we find with

kmpfit in attribute xerror, which are the square-root diagonal values of

the covariance matrix in attribute covar.

The covariance matrix elements \(C_{jk}\) for best-fit parameters p can be written as:

where we used j to indicate the matrix row and k the matrix column. If j=k then:

from which follows that the square root of the diagonal elements of the covariance matrix are the estimates of the best-fit parameter uncertainties.

Note

Parameter variances and covariance between parameters can be read from a covariance matrix. This is true for any model, not just a straight line. It is also true for models that are non-linear in their parameters.

The covariance matrix C is in stored as an attribute of the ‘kmpfit.Fitter’ object The attribute is called

covar.Error estimates for best-fit parameter are stored as an attribute of the ‘kmpfit.Fitter’ object. The attribute is called

xerror

Example program kmpfit_linearreg.py

compares the analytical covariance matrix with the kmpfit version for

linear regression, using the previously derived formulas in this section.

The output of an arbitrary example run demonstrates the similarity between the

analytical and the kmpfit method:

Example: kmpfit_linearreg.py

- Compare output analytical method and kmpfit

-- Results analytical solution:

Best fit parameters: [0.57857142857143595, 5.5285714285714258]

Parameter errors weighted fit: [0.84515425472851657, 0.1889822365046136]

Parameter errors un-/relative weighted fit: [1.0696652156022404, 0.2391844135253578]

Minimum chi^2: 8.00928571429

Covariance matrix:

0.714285714286 -0.142857142857

-0.142857142857 0.0357142857143

-- Results kmpfit:

Best-fit parameters: [0.57857145533008425, 5.5285714226701863]

Parameter errors weighted fit: [ 0.84515434 0.18898225]

Parameter errors un-/relative weighted fit: [ 1.06966532 0.23918443]

Minimum chi^2: 8.00928571429

Covariance matrix:

[[ 0.71428585 -0.14285717]

[-0.14285717 0.03571429]]

We observe:

The analytical values of the best-fit parameters and those from kmpfit correspond. The same applies to the errors for the unweighted fit/fit with relative weights.

When to use weights?¶

Sometimes there is a good reason to use a fit method that can deal with weights.

Usually you assign weights if you have additional knowledge about your measurements.

Some points get more weight if they are more reliable than others. Therefore you should

expect that the best-fit parameters are different between weighted and un-weighted

fits. Also the accuracy of the results will improve, because besides the

data you are using the quality of the data.

The difference in best-fit parameters and the quality of the results is shown

with program kmpfit_compare_wei_unwei.py

Example: kmpfit_compare_wei_unwei.py

- Compare output for unweighted (unit weighting) and weighted fit

Data x: [ 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7.]

Data y: [ 6.9 11.95 16.8 22.5 26.2 33.5 41. ]

Errors: [ 0.05 0.1 0.2 0.5 0.8 1.5 4. ]

-- Results kmpfit unit weighting wi=1.0:

Best-fit parameters: [0.57857145533008425, 5.5285714226701863]

Parameter errors weighted fit: [ 0.84515434 0.18898225]

Minimum chi^2: 8.00928571429

Covariance matrix:

[[ 0.71428585 -0.14285717]

[-0.14285717 0.03571429]]

-- Results kmpfit with weights:

Best-fit parameters: [1.8705399823164173, 5.0290902421858439]

Parameter errors weighted fit: [ 0.09922304 0.06751229]

Minimum chi^2: 4.66545480308

Covariance matrix:

[[ 0.00984521 -0.00602421]

[-0.00602421 0.00455791]]

If you examine the residuals function in this program, you will observe

that we use a weight of \(1/err_i\) in the residuals function, which is squared by kmpfit,

so in fact the weighting is \(1/\sigma_i^2\).

First we set all the errors to 1.0. This is called unit weighting and effectively

this fit does not weight at all.

The second fit has different weights.

Important is the observation that these weights can be relative.

Then they contain information about the quality of the data but do not necessarily

contain correct information about the errors on the data points and therefore

give incorrect errors on the parameter estimates.

This is shown in the same

program kmpfit_compare_wei_unwei.py

where we scaled the errors with a factor 10. The errors in the parameter estimates

are increased by a factor 10.

Example: kmpfit_compare_wei_unwei.py

- Compare output for unweighted (unit weighting) and weighted fit

-- Results kmpfit with scaled individual errors (factor=10):

Best-fit parameters: [1.870539984453957, 5.0290902408769238]

Parameter errors weighted fit: [ 0.99223048 0.6751229 ]

Minimum chi^2: 0.0466545480308

Covariance matrix:

[[ 0.98452132 -0.60242076]

[-0.60242076 0.45579092]]

This demonstrates that if weights are relative or when unit weighting is applied, one cannot rely on the covariance errors to represent real errors on the parameter estimates. The covariance errors are still based on a change in \(\chi^2\) of 1.0, but the weights do not represent the variances of the data correctly.

To summarize the weighting schemes:

Unweighted or unit weighting. Set \(w_i=1/\sigma_i^2\) to 1.0

Relative weighting. Set \(w_i=1/\sigma_i^2\) but the errors on the parameter estimates in kmpfit’s attribute

xerrorcannot be used.Statistical weighting. Set \(w_i=1/\sigma_i^2\). The errors on the parameter estimates in kmpfit’s attribute

xerrorare correct. An important assumption of this method is that the error distribution of the measured data is Gaussian and that the data errors are measured accurately (absolute uncertainties).Other weighting schemes like Poisson weighting \(w_i=1/y_i\)

Reduced chi squared¶

>From the theory of maximum likelihood we find that for a least squares solution we need to maximize the probability that a measurement \(y_i\) with given \(\sigma_i\) is in a a small interval \(dy_i\) around \(y_i\) by minimizing the sum chi squared [Ds1] :

with:

N is the number of data points

\(y_i\) the measured data at \(x_i\)

\(\sigma_i\) is the standard deviation of measurement i

f is the model for which we want to find the best-fit parameters.

The sum is often called chi squared because it follows the \(\chi^2\) distribution if we repeat the experiment to get new measurements. The expectation value of \(\chi^2\) is (see proof in [Ds3]):

where n is the number of free parameters in the fit. The reduced chi squared \(\chi_{\nu}^2\) is defined as:

where \(\nu = N-n\). From (27) we derive for the expectation value of \(\chi_{\nu}^2\):

Fitting with (26) as objective function is often called

chi squared fitting. The value of \(\chi^2_{\nu}\) is a measure of

the goodness of fit and is returned by kmpfit in a Fitter object as

attribute rchi2_min. The number of degrees of freedom is stored

in attribute dof.

Note

\(\chi_{\nu}^2\) follows the chi square statistic. This statistic measures both the spread of the data and the accuracy of the fit.

The reduced chi squared \(\chi_{\nu}^2\) is a measure of the goodness of fit. Its expectation value is 1.

A value of \(\chi_{\nu}^2 \approx 1\) indicates that there is a match between measurements, best-fit parameters and error variances.

A large value of \(\chi_{\nu}^2\) (e.g. > 1.5) indicates a poor model fit.

A \(\chi_{\nu}^2 < 1\) indicates that probably the error variance has been over-estimated.

A \(\chi_{\nu}^2 > 1\) indicates that probably the error variance has been under-estimated.

In the literature we find relations between the standard deviation of the sample and the true standard deviation of the underlying distribution . For least squares analysis we replace the average value of y (i.e. \(\bar{y}\)) in those formulas by the model with the best-fit parameters \(f(p,x)\).

What should we expect of the variance \(\sigma_i\) compared to the sample deviations for each sample point? Assume we have N data points and each data point has an individual error of \(\sigma_i\). >From (27) we have:

With the observation that the expectation value of each of the N terms is the same we derive for each data point:

So for a good fit the true deviation of a measurement \(\sigma_i\) for large N is almost equal to the deviation between data point and fit. The less the scatter of data about the best fit, the smaller \(\sigma_i\) should be.

The sample variance, \(s_y^2\) is then written as [Ds2] :

If we replace all \(\sigma_i\) with \(\sigma_y\) in equation (30), then we derive a familiar relationship:

so that the value of \(s_y^2\) of the measurements is an unbiased estimate of the true variance \(\sigma_y^2\) of the underlying distribution. For an unbiased estimator, the expected value and the true value are the same.

The weighted version of the sample variance is defined as:

If we use \(1/\sigma_i^2\) as weight, then:

Bevington [Bev] defines the weighted average of the individual variances \(\bar{\sigma}_i^2\) as:

Then:

If we set all weights to the same value \(w_i=1/\sigma_y^2\) then \(sw_y = s_y\) and:

which is consistent with (33).

For chi squared fitting it is therefore important to have correct values for \(\sigma_i\).

Over-estimated values give a \(\chi^2_{\nu}\) which is smaller than 1 and

under-estimated values give a value bigger than 1 (If you get very large values,

then probably fit and data are not in agreement). If the values for \(\sigma_i\)

are unreliable then also the error estimates of the best-fit parameters are unreliable,

because they are functions of \(\sigma_i\) (see e.g. the analytical

expressions for these errors in a linear regression in (22)).

According to equations (37) and (38) it is

reasonable then to scale the values of \(\sigma_i\) in a way that we

force \(\chi^2_{\nu}\) to take its expectation value of 1.

Then one gets values for the errors in stderr which are insensitive

to arbitrary scaling factors of the weights.

We noted earlier that scaling the weights does not change the values of the

best-fit parameters but they affect the values of the parameter error

estimates because they depend on the values of \(\sigma_i\).

If for example values of \(\sigma_i\) are all too small with a factor

2 with respect to those that make \(\chi_{\nu} =1\).

Then the errors in the parameter estimates are to small with a

factor 2x2=4 (see e.g. (19) and (21) for

the straight line model).

The value of \(\chi_{\nu}\) will be 2x2=4. So to correct the

errors on the parameter estimates, we can multiply the variances

with the value of \(\chi_{\nu}\).

If we recall equation (25), then we see that this scaling

can be applied to arbitrary models.

This scaling is exactly what happens in kmpfit for the values in attribute

stderr.

In kmpfit we use the unit- or relative weights as given by the user and calculate

the value of \(\chi_{\nu}\). The asymptotic standard errors in

xerror are then multiplied by the square root of the value

of \(\chi_{\nu}\) and stored in attribute stderr. We demonstrate

this with the output of a small example

(kmpfit_compare_wei_unwei.py)

with data from [Wol]:

Example: kmpfit_compare_wei_unwei.py

- Compare output for unweighted (unit weighting) and weighted fit

Data x: [ 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7.]

Data y: [ 6.9 11.95 16.8 22.5 26.2 33.5 41. ]

Errors: [ 0.05 0.1 0.2 0.5 0.8 1.5 4. ]

New array with measurement errors, scaled with factor 0.933091 to give

a reduced chi-squared of 1.0:

[ 0.04829832 0.09659663 0.19319327 0.48298317 0.77277307 1.4489495

3.86386534]

-- Results kmpfit with scaled individual errors to force red_chi2=1:

Best-fit parameters: [1.8705399822570359, 5.029090242191204]

Parameter errors using measurement uncertainties: [ 0.09584612 0.0652146 ]

Parameter errors unit-/relative weighted fit: [ 0.09584612 0.0652146 ]

Minimum chi^2: 5.0

Minimum reduced chi^2: 1.0

Covariance matrix:

[[ 0.00918648 -0.00562113]

[-0.00562113 0.00425294]]

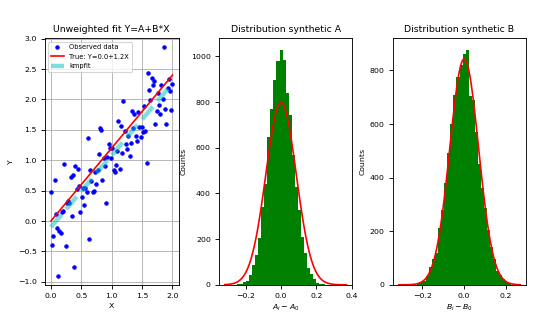

The next code example is a small script that shows that the scaled error estimates

in attribute stderr for unit- and relative weighting are realistic if we

compare them to errors found with a Monte Carlo method.

We start with values of \(\sigma_i\) that are under-estimated. This

results in a value for \(\chi_{\nu}\) which is too low. The re-scaled

errors in stderr match with those that are estimated with the Monte-Carlo method.

In the example we used the Bootstrap Method.

The plot shows the fit and the bootstrap distributions of parameter A and B.

We will explain the Bootstrap Method in the next section.

Example: kmpfit_unweighted_bootstrap_plot.py - How to deal with unweighted fits

#!/usr/bin/env python

#------------------------------------------------------------

# Purpose: Demonstrate that the scaled covariance errors for

# unweighted fits are comparable to errors we find with

# a bootstrap method.

# Vog, 24 Nov 2011

#------------------------------------------------------------

import numpy

from matplotlib.pyplot import figure, show, rc

from numpy.random import normal, randint

from kapteyn import kmpfit

# Residual and model in 1 function. Model is straight line

def residuals(p, data):

x, y, err = data

a, b = p

model = a + b*x

return (y-model)/err

# Artificial data

N = 100

a0 = 0; b0 = 1.2

x = numpy.linspace(0.0, 2.0, N)

y = a0 + b0*x + normal(0.0, 0.4, N) # Mean,sigma,N

err = numpy.ones(N) # All weights equal to 1

# Prepare fit routine

fitobj = kmpfit.Fitter(residuals=residuals, data=(x, y, err))

try:

fitobj.fit(params0=[1,1])

except Exception as mes:

print("Something wrong with fit: ", mes)

raise SystemExit

print("\n\n======== Results kmpfit unweighted fit =========")

print("Params: ", fitobj.params)

print("Errors from covariance matrix : ", fitobj.xerror)

print("Uncertainties assuming reduced Chi^2=1: ", fitobj.stderr)

print("Chi^2 min: ", fitobj.chi2_min)

print("Reduced Chi^2: ", fitobj.rchi2_min)

print("Iterations: ", fitobj.niter)

print("Function ev: ", fitobj.nfev)

print("Status: ", fitobj.status)

print("Status Message:", fitobj.message)

# Bootstrap method to find uncertainties

A0, B0 = fitobj.params

xr = x.copy()

yr = y.copy()

ery = err.copy()

fitobj = kmpfit.Fitter(residuals=residuals, data=(xr, yr, ery))

slopes = []

offsets = []

trials = 10000 # Number of synthetic data sets

for i in range(trials): # Start loop over pseudo sample

indx = randint(0, N, N) # Do the resampling using an RNG

xr[:] = x[indx]

yr[:] = y[indx]

ery[:] = err[indx]

# Only do a regression if there are at least two different

# data points in the pseudo sample

ok = (xr != xr[0]).any()

if (not ok):

print("All elements are the same. Invalid sample.")

print(xr, yr)

else:

fitobj.fit(params0=[1,1])

offs, slope = fitobj.params

slopes.append(slope)

offsets.append(offs)

slopes = numpy.array(slopes) - B0

offsets = numpy.array(offsets) - A0

sigmaA0, sigmaB0 = offsets.std(), slopes.std()

print("Bootstrap errors in A, B:", sigmaA0, sigmaB0)

# Plot results

rc('font', size=7)

rc('legend', fontsize=6)

fig = figure(figsize=(7,4))

fig.subplots_adjust(left=0.08, wspace=0.3, right=0.94)

frame = fig.add_subplot(1,3,1, aspect=1.0, adjustable='datalim')

frame.plot(x, y, 'bo', ms=3, label='Observed data')

frame.plot(x, a0+b0*x, 'r', label='True: Y=%.1f+%.1fX'%(a0,b0))

frame.plot(x, A0+B0*x, '--c', alpha=0.5, lw=4, label='kmpfit')

frame.set_xlabel("X"); frame.set_ylabel("Y")

frame.set_title("Unweighted fit Y=A+B*X")

frame.grid(True)

frame.legend(loc='upper left')

ranges = [(offsets.min(), offsets.max()),(slopes.min(), slopes.max())]

nb = 40 # Number of bins in histogram

for i,sigma in enumerate([sigmaA0, sigmaB0]):

framehist = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 2+i)

range = ranges[i] # (X) Range in histogram

framehist.hist(slopes, bins=nb, range=range, fc='g')

binwidth = (range[1]-range[0])/nb # Get width of one bin

area = trials * binwidth # trials is total number of counts

mu = 0.0

amplitude = area / (numpy.sqrt(2.0*numpy.pi)*sigma)

x = numpy.linspace(range[0], range[1], 100)

y = amplitude * numpy.exp(-(x-mu)*(x-mu)/(2.0*sigma*sigma))

framehist.plot(x, y, 'r')

if i == 0:

lab = "$A_i-A_0$"

title = "Distribution synthetic A"

else:

lab = "$B_i-B_0$"

title = "Distribution synthetic B"

framehist.set_xlabel(lab)

framehist.set_ylabel("Counts")

framehist.set_title(title)

show()

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

Bootstrap Method¶

We need to discuss the bootstrap method, that we used in the last script, in some detail. Bootstrap is a tool which estimates standard errors of parameter estimates by generating synthetic data sets with samples drawn with replacement from the measured data and repeating the fit process with this synthetic data.

Your data realizes a set of best-fit parameters, say \(p_{(0)}\). This data set is one of many different data sets that represent the ‘true’ parameter set \(p_{true}\) . Each data set will give a different set of fitted parameters \(p_{(i)}\). These parameter sets follow some probability distribution in the n dimensional space of all possible parameter sets. To find the uncertainties in the fitted parameters we need to know the distribution of \(p_{(i)}-p_{true}\) [Num]. In Monte Carlo simulations of synthetic data sets we assume that the shape of the distribution of Monte Carlo set \(p_{(i)}-p_{0}\) is equal to the shape of the real world set \(p_{(i)}-p_{true}\)

The Bootstrap Method [Num] uses the data set that you used to find the best-fit parameters. We generate different synthetic data sets, all with N data points, by randomly drawing N data points, with replacement from the original data. In Python we realize this as follows:

indx = randint(0, N, N) # Do the re-sampling using an RNG

xr[:] = x[indx]

yr[:] = y[indx]

ery[:] = err[indx]

We create an array with randomly selected array indices in the range 0 to N.

This index array is used to create new arrays which represent our synthetic data.

Note that for the copy we used the syntax xr[:] with the colon, because we want to

be sure that we are using the same array xr, yr and ery each time, because

the fit routine expects the data in these arrays (and not copies of them with the same name).

The synthetic data arrays will consist of about 37 percent duplicates. With these

synthetic arrays we repeat the fit and find our \(p_{(i)}\). If we repeat this

many times (let’s say 1000), then we get the distribution we needed. The standard

deviation of this distribution (i.e. for one parameter), gives the uncertainty.

Note

The bigger the data set, the higher the number of bootstrap trials should be to get accurate statistics. The best way to find a minimum number is to plot the Bootstrap results as in the example.

Jackknife method¶

Another Monte Carlo method is the Jackknife method. The Jackknife method finds errors on best-fit parameters of a model and N data points using N samples. In each sample a data point is left out, starting with the first, then the second and so on. For each of these samples we do a fit and store the parameters. For example, for a straight line we store the slopes and offsets. If we concentrate on one parameter and call this parameter \(\theta\) then for each run i we find the estimated slope \(\theta_i\). The average of all the slopes is \(\bar{\theta^*})\). Then the Jackknife error is:

Notes about weighting¶

Unweighted (i.e. unit weighting) and relative weighted fits

For unit- or relative weighting, we find errors that correspond to attribute

stderrin kmpfit.The errors on the best-fit parameters are scaled (internally) which is equivalent to scaling the weights in a way that the value of the reduced chi-squared becomes 1.0

For unweighted fits, the standard errors from

Fitter.stderrare comparable to errors we find with Monte Carlo simulations.

Alper, [Alp] states that for some combinations of model, data and weights,

the standard error estimates from diagonal elements of the covariance

matrix neglect the interdependencies between parameters and lead

to erroneous results. Often the measurement errors are difficult to obtain precisely,

sometimes these errors are not normally distributed. For this category of

weighting schemes, one should always inspect the covariance matrix (attribute

covar) to get an idea how big the covariances are with respect to

the variances (diagonal elements of the matrix).

The off-diagonal elements of the covariance matrix should be

much lower than the diagonal.

Weighted fits with weights derived from real measurement errors

For weighted fits where the weigths are derived from measurement errors, the errors correspond to attribute

xerrorin kmpfit. Only for this type of weights, we get a value of (reduced) chi-squared that can be used as a measure of goodness of fit.The fit results depend on the accuracy of the measurement errors \(\sigma_i.\)

A basic assumption of the chi-squared objective function is that the error distribution of the measured data is Gaussian. If this assumption is violated, the value of chi squared does not make sense.

The uncertainties given in attribute

xerrorandstderrare the same, only when \(\chi_{\nu}^2 = 1\)

>From [And] we summarize the conditions which must be met before one can

safely use the values in stderr (i.e. demanding that \(\chi_{\nu} = 1\)):

In this approach of scaling the error in the best-fit parameters,

we make some assumptions:

The error distribution has to be Gaussian.

The model has to be linear in all parameters. If the model is nonlinear, we cannot demand that \(\chi_{\nu} = 1\), because the derivation of \(\langle\chi\rangle^2=N-n\) implicitly assumes linearity in all parameters.

By demanding \(\chi_{\nu} = 1\), we explicitly claim that the model we are using is the correct model that corresponds to the data. This is a rather optimistic claim. This claim requires justification.

Even if all these assumptions above are met, the method is in fact only applicable if the degrees of freedom N-n is large. The reason is that the uncertainty in the measured data data does not only cause an uncertainty in the model parameters, but also an uncertainty in the value of \(\chi^2\) itself. If N-n is small, \(\chi^2\) may deviate substantially from N-n even though the model is linear and correct.

The conclusion is that one should be careful with the use of standard errors

in stderr. A Monte Carlo method should be applied to prove that the

values in stderr can be used.

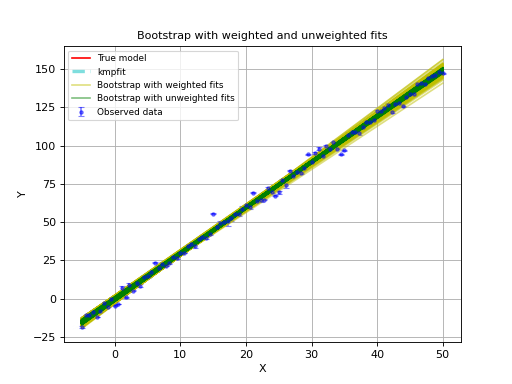

For weighted fits it is advertised not to use the Bootstrap method.

In the next example we compare the Bootstrap method with and without weights.

The example plots all trial results in the Bootstrap procedure.

The yellow lines represent weighted fits in the Bootstrap procedure.

The green lines represent unweighted fits in the Bootstrap procedure.

One can observe that the weighted version shows errors that are much too big.

Example: kmpfit_weighted_bootstrap.py

- Compare Bootstrap with weighted and unweighted fits

======== Results kmpfit UNweighted fit =========

Params: [-0.081129823700123893, 2.9964571786959704]

Errors from covariance matrix : [ 0.12223491 0.0044314 ]

Uncertainties assuming reduced Chi^2=1: [ 0.21734532 0.00787946]

Chi^2 min: 626.001387167

Reduced Chi^2: 3.16162316751

Iterations: 2

Function ev: 7

Status: 1

======== Results kmpfit weighted fit =========

Params: [-1.3930156818836363, 3.0345053718712571]

Errors from covariance matrix : [ 0.01331314 0.0006909 ]

Uncertainties assuming reduced Chi^2=1: [ 0.10780843 0.00559485]

Chi^2 min: 12984.0423449

Reduced Chi^2: 65.575971439

Iterations: 3

Function ev: 7

Status: 1

Covariance matrix: [[ 1.77239564e-04 -6.78626129e-06]

[ -6.78626129e-06 4.77344773e-07]]

===== Results kmpfit weighted fit with reduced chi^2 forced to 1.0 =====

Params: [-1.3930155828717012, 3.034505368057717]

Errors from covariance matrix : [ 0.10780841 0.00559485]

Uncertainties assuming reduced Chi^2=1: [ 0.10780841 0.00559485]

Chi^2 min: 198.0

Reduced Chi^2: 1.0

Iterations: 3

Function ev: 7

Status: 1

Bootstrap errors in A, B for procedure with weighted fits: 0.949585141866 0.0273199443168

Bootstrap errors in A, B for procedure with unweighted fits: 0.217752459166 0.00778497229684

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

The same conclusion applies to the Jackknife method. For unweighted fits, the Jackknife error estimates are very good, but for weighted fits, the method can not be used. This can be verified with the example script below. [Sha] proposes a modified Jackknife method to improve the error estimates.

Example: kmpfit_weighted_jackknife.py

- Compare Jackknife with weighted and unweighted fits

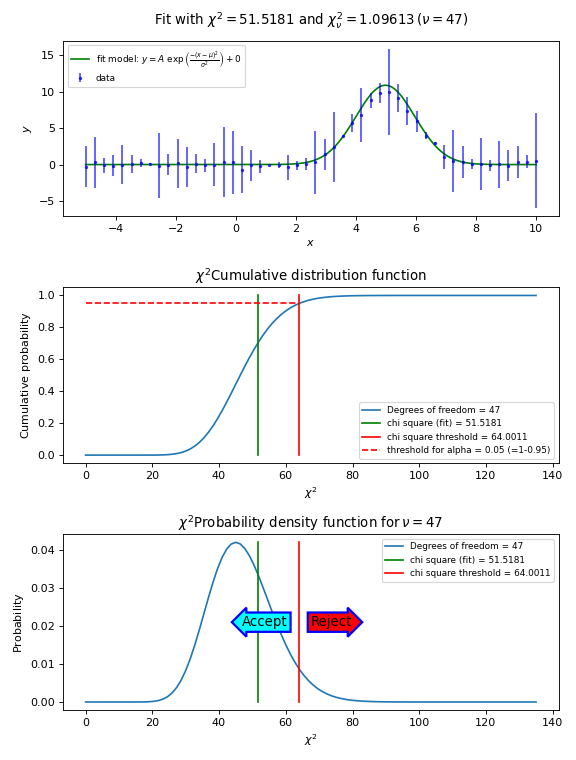

Goodness of fit¶

Chi-squared test¶

As described in a previous section, the value of the reduced chi-squared is an indication for the goodness of fit. If its value is near 1 then your fit is probably good. With the value of chi-squared we can find a threshold value for which we can accept or reject the hypothesis that the data and the fitted model are consistent. The assumption is that the value of chi-squared follows the \(\chi^2\) distribution with \(\nu\) degrees of freedom. Let’s examine chi-squared in more detail.

In a chi-squared fit we sum the relative size of the deviation \(\Delta_i\) and the error bar \(\delta_i\). Data points that are near the fit with the best-fit parameters have a small value \(\Delta_i/\delta_i\). Bad points have a ratio that is bigger than 1. At those points the fitted curve does not go through the error bar. For a reasonable fit, there will be both small and big deviations but on average the value will be near 1. Remember that chi-squared is defined as:

So if we expect that on average the ratios are 1, then we expect that this sum is equal to N. You can always add more parameters to a model. If you have as many parameters as data points, you can find a curve that hits all data points, but usually these curves have no significance. In this case you don’t have any degrees of freedom. The degrees of freedom for a fit with N data points and n adjustable model parameters is:

To include the degrees of freedom, we define the reduced chi squared as:

In the literature ([Ds3]) we can find prove that the expectation value of the reduced chi squared is 1. If we repeat a measurement many times, then the measured values of \(\chi^2\) are distributed according to the chi-squared distribution with \(\nu\) degrees of freedom. See for example http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chi-squared_distribution.

We reject the null hypothesis (data is consistent with the model with the

best fit parameters) if the value of chi-squared is bigger than some threshold value.

The threshold value can be calculated if we set a value of the probability that

we make a wrong decision in rejecting a true null hypothesis (H0). This

probability is denoted by \(\alpha\) and it sets the

significance level of the test. Usually we want small values for \(\alpha\)

like 0.05 or 0.01. For a given value of \(\alpha\) we calculate

\(1-\alpha\), which is the left tail area under the cumulative distribution

function. This probability is calculated with scipy.stats.chi2.cdf().

If \(\alpha\) is given and we want to know the threshold value for

chi-squared, then we use the Percent Point Function scipy.stats.chi2.ppf()

which has \(1-\alpha\) as its argument.

The recipe to obtain a threshold value for \(\chi^2\) is as follows.

- Set the hypotheses:

\(H_0\): The data are consistent with the model with the best fit parameters

\(H_{\alpha}\): The data are not consistent with the model with the best fit parameters

Make a fit and store the calculated value of \(\chi^2\)

Set a p-value (\(\alpha\))

Use the \(\chi^2\) cumulative distribution function for \(\nu\) degrees of freedom to find the threshold \(\chi^2\) for \(1-\alpha\). Note that \(\alpha\) is the right tailed area in this distribution while we use the left tailed area in our calculations.

Compare the calculated \(\chi^2\) with the threshold value.

If the calculated value is bigger, then reject the hypothesis that the data and the model with the best-fit parameters are consistent.

In the next figure we show these steps graphically. Note the use of the statistical functions and methods from SciPy.

Example: kmpfit_goodnessoffit1.py - Goodness of fit based on the value of chi-squared

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

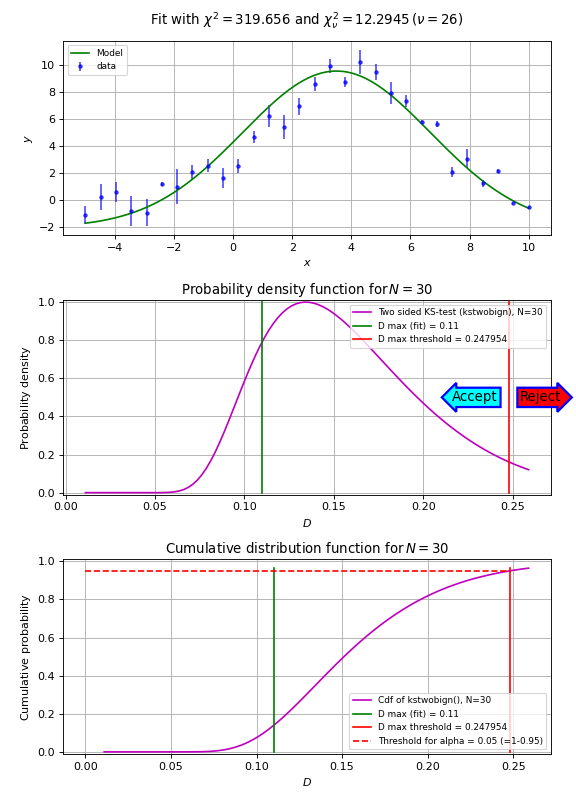

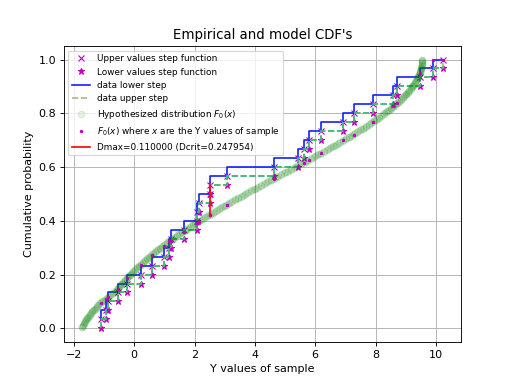

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test¶

Another goodness-of-fit test is constructed by using the critical values of the Kolmogorov distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test [Mas] ).

For this test we need the normalized cumulative versions of the data and the model with the best-fit parameters. We call the cumulative distribution function of the model \(F_0(x)\) and the observed cumulative distribution function of our data sample \(S_n(x)\) then the sampling distribution of \(D = \max| F_0(x) - S_n(x) |\) follows the Kolmogorov distribution which is independent of \(F_0(x)\) if \(F_0(x)\) is continuous, i.e. has no jumps.

The cumulative distribution of the sample is called the empirical distribution function (ECDF). To create the ECDF we need to order the sample values \(y_0, y_1, ..., y_n\) from small to high values. Then the ECDF is defined as:

The value of \(n(i)\) is the number of sample values \(y\) that are smaller than or equal to \(y_i\). So the first value would be 1/N, the second 2/N etc.

The cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the model can be calculated in the same way. First we find the best-fit parameters for a model using kmpfit. Select a number of X values to find Y values of your model. Usually the number of model samples is much higher than the number of data samples. With these (model) Y values we create a CDF using the criteria (ordered Y values) of the data. If dat1 are the ordered sample Y values and dat2 are the ordered model Y values, then a function that calculates the CDF could be:

def cdf(Y_ord_data, Y_ord_model):

cdfnew = []

n = len(Y_ord_model)

for yy in Y_ord_data:

fr = len(Y_ord_model[Y_ord_model <= yy])/float(n)

cdfnew.append(fr)

return numpy.asarray(cdfnew)

which is not the most efficient procedure but it is simple and it just works.

For hypotheses testing we define:

\(H_0\): The data are consistent with the model with the best fit parameters

\(H_{\alpha}\): The data are not consistent with the model with the best fit parameters

Note that the ECDF is a step function and this step function could be interpreted in two ways. Therefore the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test statistic is defined as:

where we note that \(F_0\) is a continuous distribution function (a requirement for the KS-test).

The null hypothesis is rejected at a critical probability \(\alpha\) (confidence level) if \(D_n > D_{\alpha}\). The value \(D_{\alpha}\) is a threshold value. Given the value of \(\alpha\), we need to find \(D_{\alpha}\) by solving:

To find this probability we use the Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sided test which

can be approximated with SciPy’s method scipy.stats.kstwobign().

This test uses \(D_n/\sqrt(N)\) as input and the output of kstwobign.ppf()

is \(D_n*\sqrt(N)\). Given a value for N, we find threshold values for

\(D_n\) for frequently used values of confidence level \(\alpha\), as

follows:

N = ...

from scipy.stats import kstwobign

# Good approximation for the exact distribution if N>4

dist = kstwobign()

alphas = [0.2, 0.1, 0.05, 0.025, 0.01]

for a in alphas:

Dn_crit = dist.ppf(1-a)/numpy.sqrt(N)

print("Critical value of D at alpha=%.3f(two sided): %g"%(a, Dn_crit))

In the next script we demonstrate that the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test is useful if we have reasonable fits, but bad values of chi-squared due to improperly scaled errors on the data points. The \(\chi^2\) test will immediately reject the hypothesis that data and model are consistent. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test depends on the difference between the cumulative distributions and does not depend on the scale of these errors. The empirical and model cdf’s show where the fit deviates most from the model. A plot with these cdf’s can be a starting point to reconsider a model if the deviations are too large.

Example: kmpfit_goodnessoffit2.py - Kolmogorov-Smirnov goodness of fit test

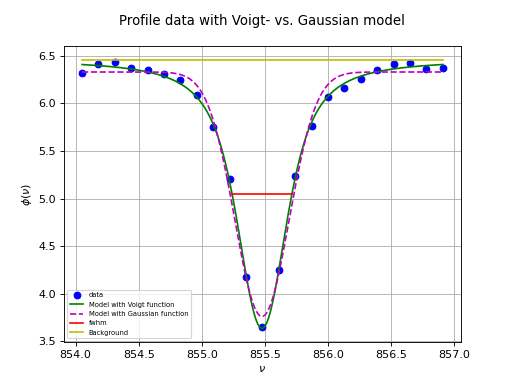

Profile fitting¶

Gaussian profiles¶

There are many examples where an astronomer needs to know the characteristics of a Gaussian profile. Fitting best parameters for a model that represents a Gauss function, is a way to obtain a measure for the peak value, the position of the peak and the width of the peak. It does not reveal any skewness or kurtosis of the profile, but often these are not important. We write the Gauss function as:

Here \(A\) represents the peak of the Gauss, \(\mu\) the mean, i.e. the position of the peak and \(\sigma\) the width of the peak. We added \(z_0\) to add a background to the profile characteristics. In the early days of fitting software, there were no implementations that did not need partial derivatives to find the best fit parameters.

Partial derivatives for a Gaussian¶

In the documentation of the IDL version of mpfit.pro, the author states that it is often sufficient and even faster to allow the fit routine to calculate the derivatives numerically. In contrast with this we usually gain an increase in speed of about 20% if we use explicit partial derivatives, at least for fitting Gaussian profiles. The real danger in using explicit partial derivatives seems to be that one easily makes small mistakes in deriving the necessary equations. This is not always obvious in test-runs, but kmpfit is capable of providing diagnostics. For the Gauss function in (46) we derived the following partial derivatives:

If we want to use explicit partial derivatives in kmpfit we need the external residuals

to return the derivative of the model f(x) at x, with respect to any of the parameters.

If we denote a parameter from the set of parameters \(P = (A,\mu,\sigma,z_0)\)

with index i, then one calculates

the derivative with a function FGRAD(P,x,i).

In fact, kmpfit needs the derivative of the residuals and if we defined the residuals

as residuals = (data-model)/err, the residuals function should return:

where err is the array with weights.

Below, we show a code example of how one can implement explicit partial derivatives.

We created a function, called my_derivs which calculates the derivatives for each

parameter. We tried to make the code efficient but you should be able to recognize

the equations from (47). The return value is equivalent with (48).

The function has a fixed signature because it is called by the fitter which expects

that the arguments are in the right order. This order is:

p -List with model parameters, generated by the fit routine

data -A reference to the

dataargument in the constructor of the Fitter object.dflags -List with booleans. One boolean for each model parameter. If the value is

Truethen an explicit partial derivative is required. The list is generated by the fit routine.

There is no need to process the dflags list in your code. There is no problem if

you return all the derivatives even when they are not necessary.

Note

A function which returns derivatives should create its own work array to store the calculated values. The shape of the array should be (parameter_array.size, x_data_array.size).

The function my_derivs is then:

def my_derivs(p, data, dflags):

#-----------------------------------------------------------------------

# This function is used by the fit routine to find the values for

# the explicit partial derivatives. Argument 'dflags' is an array

# with booleans. If an element is True then an explicit partial

# derivative is required.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------------

x, y, err = data

A, mu, sigma, zerolev = p

pderiv = numpy.zeros([len(p), len(x)]) # You need to create the required array

sig2 = sigma*sigma

sig3 = sig2 * sigma

xmu = x-mu

xmu2 = xmu**2

expo = numpy.exp(-xmu2/(2.0*sig2))

fx = A * expo

for i, flag in enumerate(dflags):

if flag:

if i == 0:

pderiv[0] = expo

elif i == 1:

pderiv[1] = fx * xmu/(sig2)

elif i == 2:

pderiv[2] = fx * xmu2/(sig3)

elif i == 3:

pderiv[3] = 1.0

return pderiv/-err

Note that all the values per parameter are stored in a row. A minus sign is added to

to the error array to fulfill the

requirement in equation (48).

The constructor of the Fitter object is as follows (the function my_residuals is

not given here):

fitobj = kmpfit.Fitter(residuals=my_residuals, deriv=my_derivs, data=(x, y, err))

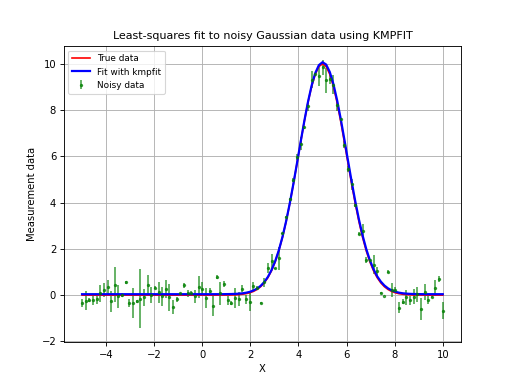

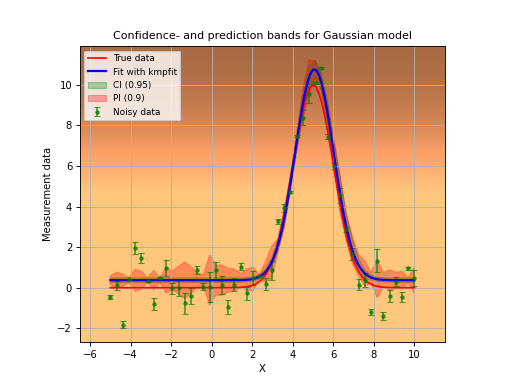

The next code and plot show an example of finding and plotting best fit parameters given a Gauss

function as model. If you want to compare the speed between a fit with explicit partial derivatives

and a fit using numerical derivatives, add a second Fitter object by omitting the deriv argument.

In our experience, the code with the explicit partial derivatives is about 20% faster because it

needs considerably fewer function calls to the residual function.

Example: kmpfit_example_partialdervs.py - Finding best fit parameters for a Gaussian model

#!/usr/bin/env python

#------------------------------------------------------------

# Script compares efficiency of automatic derivatives vs

# analytical in mpfit.py

# Vog, 31 okt 2011

#------------------------------------------------------------

import numpy

from matplotlib.pyplot import figure, show, rc

from kapteyn import kmpfit

def my_model(p, x):

#-----------------------------------------------------------------------

# This describes the model and its parameters for which we want to find

# the best fit. 'p' is a sequence of parameters (array/list/tuple).

#-----------------------------------------------------------------------

A, mu, sigma, zerolev = p

return( A * numpy.exp(-(x-mu)*(x-mu)/(2.0*sigma*sigma)) + zerolev )

def my_residuals(p, data):

#-----------------------------------------------------------------------

# This function is the function called by the fit routine in kmpfit

# It returns a weighted residual. De fit routine calculates the

# square of these values.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------------

x, y, err = data

return (y-my_model(p,x)) / err

def my_derivs(p, data, dflags):

#-----------------------------------------------------------------------

# This function is used by the fit routine to find the values for

# the explicit partial derivatives. Argument 'dflags' is a list

# with booleans. If an element is True then an explicit partial

# derivative is required.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------------

x, y, err = data

A, mu, sigma, zerolev = p

pderiv = numpy.zeros([len(p), len(x)]) # You need to create the required array

sig2 = sigma*sigma

sig3 = sig2 * sigma

xmu = x-mu

xmu2 = xmu**2

expo = numpy.exp(-xmu2/(2.0*sig2))

fx = A * expo

for i, flag in enumerate(dflags):

if flag:

if i == 0:

pderiv[0] = expo

elif i == 1:

pderiv[1] = fx * xmu/(sig2)

elif i == 2:

pderiv[2] = fx * xmu2/(sig3)

elif i == 3:

pderiv[3] = 1.0

pderiv /= -err

return pderiv

# Artificial data

N = 100

x = numpy.linspace(-5, 10, N)

truepars = [10.0, 5.0, 1.0, 0.0]

p0 = [9, 4.5, 0.8, 0]

y = my_model(truepars, x) + 0.3*numpy.random.randn(len(x))

err = 0.3*numpy.random.randn(N)

# The fit

fitobj = kmpfit.Fitter(residuals=my_residuals, deriv=my_derivs, data=(x, y, err))

try:

fitobj.fit(params0=p0)

except Exception as mes:

print("Something wrong with fit: ", mes)

raise SystemExit

print("\n\n======== Results kmpfit with explicit partial derivatives =========")

print("Params: ", fitobj.params)

print("Errors from covariance matrix : ", fitobj.xerror)

print("Uncertainties assuming reduced Chi^2=1: ", fitobj.stderr)

print("Chi^2 min: ", fitobj.chi2_min)

print("Reduced Chi^2: ", fitobj.rchi2_min)

print("Iterations: ", fitobj.niter)

print("Function ev: ", fitobj.nfev)

print("Status: ", fitobj.status)

print("Status Message:", fitobj.message)

print("Covariance:\n", fitobj.covar)

# Plot the result

rc('font', size=9)

rc('legend', fontsize=8)

fig = figure()

frame = fig.add_subplot(1,1,1)

frame.errorbar(x, y, yerr=numpy.abs(err), fmt='go', alpha=0.7, ms=2, label="Noisy data")

frame.plot(x, my_model(truepars,x), 'r', label="True data")

frame.plot(x, my_model(fitobj.params,x), 'b', lw=2, label="Fit with kmpfit")

frame.set_xlabel("X")

frame.set_ylabel("Measurement data")

frame.set_title("Least-squares fit to noisy Gaussian data using KMPFIT",

fontsize=10)

frame.grid()

leg = frame.legend(loc=2)

show()

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

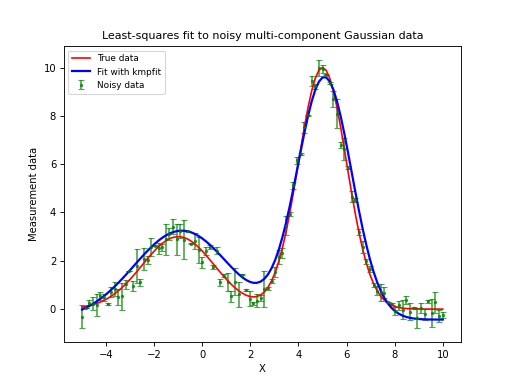

Automatic initial estimates for profiles with multi component Gaussians¶

For single profiles we can obtain reasonable initial estimates by inspection of the profile. Processing many profiles, e.g. in a data cube with two spatial axes and one spectral axis, needs another approach. If your profile has more than 1 Gaussian component, the problem becomes even more complicated. So what we need is a method that automates the search for reasonable initial estimates.

Gauest¶

Function profiles.gauest() is a function which can be used to get basic characteristics of

a Gaussian profile. The number of Gaussian components in that profile can be

greater than 1. These characteristics are amplitude, position of the maximum

and dispersion. They are very useful

as initial estimates for a least squares fit of this type of

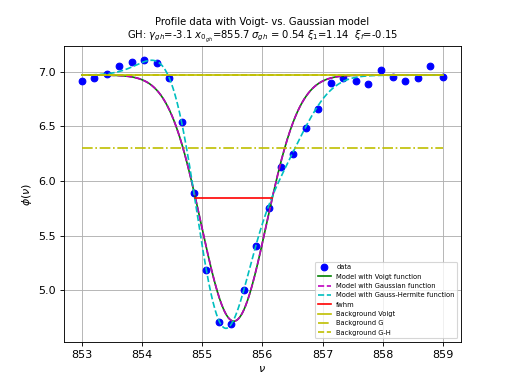

multi-component Gausian profiles.